This popular blog is an update from my old site, which attracted hundreds of reads. I have just finished my latest lithography, and found my previous notes very helpful, hence they can now be consolidated below.

What is Lithography?

Lithography is a process of printing on the flat surface of a stone using a simple principle: oil and water don't mix. You draw on a stone surface which is receptive to grease and then treat the surface chemically with gum arabic and a nitric acid etching solution. The 'etch' solution does not bite into the surface like in copper plate etching - it only chemically separates the greasy image and water attracting non-image.

Lithography was invented by accident in Germany around 1796. Playwright Alois Senefelder discovered that he could duplicate his scripts by writing them in greasy crayon on slabs of limestone and then printing them with rolled-on ink. We still print on limestone today, and even after repeated inking and printing, lithographs (so called from the Latin for stone, litho, and mark, graph) can be printed in almost unlimited quantities.

The easy production and economical distribution meant that lithography found a place in commercial and artistic practices. As a means of multiplying drawings it has been embraced by many great artists over the centuries. I was surprised when I looked through a lithography book in class how many famous artists have explored the lithography medium. The following are a couple of historic artists who stood out to me.

How to make a Lithograph

Getting to know your stone

First select a stone and check that hasn't been already allocated to another student in the studio! Sign your stone number into the register sheet and check to see if there are any notes on the specifics of your stone. Then give your stone a nice little pat and say, 'hello, we are going to have a fun time together!'

Move the super heavy stone using a trolley and make sure you communicate as you manoeuvre it around. Sometime you might need the help of a crowbar if the stone has stuck to a surface with gum arabic. Get help from a studio buddy if you need to and make sure you keep your fingers away from getting jammed by the movement of the stone as you lift it from its shelf to the bench top and press.

Check if your stone has dips or hollows, or is the nice even surface that you need to draw and print on. To check for hollows get three little torn pieces of paper and put them on the stone. Place a steel ruler over the papers and try to pull out the papers. There should be a similar resistance to each of them. If they just fall on out, you probably have a dip or hollow. Test the stone with the ruler and papers across both diagonals and down the middles to confirm.

You can check to see if your stone is wedged by setting the pressure tight on one end of the stone feeling the pressure when lifting and pushing down the press arm. Both ends should feel similar. If one end has a lot less resistance the end would have wedge.

You can try remedy any dips, hollows or wedges through the graining process coming up.

Graining your stone

Move your stone to the graining sink, and if you have a waterproof apron, it would be a smart time to put it on now! Putting up the wooden side rails around the sink can also make this process a bit less messy.

You need to grain your stone using up to four grit coarsenesses: 80, 120, 180 and 220. There is a good chance your stone make already be grained to 120. Get the levigator (graining disc) and wet down it and the stone. Then sprinkle the grit onto the sone. If you are already at 120 (and the sign form for nominating your stone should confirm), you can start at 180 grit. Gently and carefully flip on the levigator (they are heavy!) and slowly start spinning it around the stone in the specified formation. I'm left handed, so I spun the levigator clockwise, but if you are right handed you could rotate it anticlockwise.

Use the graining pattern designated for your stone size, making sure that around the edges a third of the levigator is off the stone so that you don't create a hollow by graining too much of the middle away. If your stone already has a dip or wedge, you can concentrate more on the area that needs to be worn down to achieve a more even stone surface. This image from Peter Lancaster's book Stone Lithography (RMIT, 1997) details the correct graining patterns:

When the grit turns a milky light grey from the levigator friction, remove the levigator, wash it and the stone thoroughly, and then apply the grit again.

You need to go through the process of graining at each grit level three times before moving up to the finer grit. It is essential to wash the old grit away thoroughly before starting with the new grit, especially if you are moving to a finer grit. Having a stone grained to 220 makes for a beautiful smooth surface to work on, but if you want more stone texture to transfer to the print, you might want to only go up to 180.

Squeegee the wet stone down and then grab a medieval style leather flag and flap it until all the water of the stone is evaporated. Yes, this can take ages, and I have been known to use a hairdryer to hasten this process when I'm rushed. It is important to get rid of all the water off the stone before you start the drawing process however, or else the reticulated water marks will be seen on the print. It is also important to not touch the surface of your stone more than necessary so that greasy finger marks also don't affect the print.

It would be a wise idea to check that your stone is even after graining (or at least improved in evenness) through the rule and wedge tests before drawing.

Getting drawing!

Decide if you want a bleed print or a margin border and select a template stencil to trace around with a conte pencil (which won't print). You can freestyle the print with a organically shaped border too, you don't need to have straight lines! Paint around the edges with gum arabic so that you can keep the edges clean.

For this assignment I wanted to explore as many of the mark making techniques I could. I blocked out areas with gum arabic and mixed in ink and turps to paint with. I drew with crayons, lithograph pencils (sometimes dipped in water for a more painterly effect) and drawing sticks and painted with tusche (water and turps). I tried using rubbing inks and using paper to stencil elements for interesting effects. I scraped back with my burnishing tool, scrapper, a blade and sandpaper to experiment with deletions.

First etch

Pat the image with talc using a soft 'cloudy' cushion of rag (ensuring that there is no loose 'tail' being dragged over your work). The talc both stops greasy ink smudging and helps draw the image into the stone. Wipe gum arabic over the stone and then buff gently until it isn't sticky anymore. You have just made a protective gum absorption film over the stone!

Grab a bowl, a half sponge rung out, gum arabic, medium etch, a paint brush and some cheesecloth.

In the bowl mix 30 ml of gum arabic and 30 ml of medium etch in a 50/50 solution. Test the solution on the side of the stone away from the image and hold it under a light (such as the torch on your phone) and check how reactive it is. There should be a light bubbling for 30 seconds. If it bubbles like a head of beer it is too strong and you should put some extra gum arabic in. If there are no bubbles you need more etch in it.

Once you have the solution right, pour a third of the solution over the image (hit the darkest areas of the image first) and sponge over with the half sponge moving the solution around the stone for 30 seconds in a figure 8 movement. Do this another two times. Watch for your image disappearing - this is bad! You need to squirt some gum arabic on it to halt the etch as much as possible. Very greasy tusche areas or digital image transfers may need a stronger etch.

Lastly, buff down the stone with a soft cloudy pad of cheesecloth so it isn't sticky anymore.

Second etch with proofing

Roll up. Wipe down to clean an ink slab and get a nap roller, roller holder and two ink knives. You need a 50c piece size of two inks: Litho Crayon Ink (which is harder) and Litho Roll Up Ink (which is runny). Carefully scrap out some ink (don't dig) and mix the inks together on the slab. You want a fairly stiff ink, the temperature of the day can affect this so test and adjust as needed. Rolling up can give you blisters, so use cuffs and talc to avoid this.

Set the press. Have lots of newsprints torn to be smaller than the surface of the stone. Put one on the stone. Find a tympan (plastic backing) that fits the stone and put it on the paper on the stone, greasy side up. Find a scraper bar that fits the width of the stone and set the magnets an inch in from each side of where the stone is sitting on the press. Move the lever to start the stone moving towards the scraper. Stop an inch in. Bring down the the pressure handle, wind pressure hand-wheel to lower scraper bar until it touches the stone. Release pressure handle, rotate the pressure hand-wheel a further quarter of a turn. Check the pressure is quite firm on both ends of the stone. This is a good starting pressure, and adjustments from here should be minor. It's a good idea to get a tech to check the pressure if you are unsure.

Roll up and proofing. Get 2 x bowls, 2 x sponges, 1 x gum arabic, 2 x rags, gloves, turps, wash out solution, move the exhaust to your area and some safety glasses.

Firstly gum up your stone to reinforce the non-image areas and buff until touch dry.

Turn on the exhaust, put on your gloves and glasses and pour turps over the image to remove the grease. You should see a ghost of the image. Throw rag into the red solvent bin and then rub wash out solution (which is a combo of bitumen and turps) on a rag just the image area. This replaces the drawing materials with grease. Buff off the excess bitumen so it is a smooth even coating. I think this step seems magical - I love seeing the ghost image reappear!

Chuck the used rag in the red solvent bin and flood the stone with water to dissolve the gum and allow the grease to float to the top. Remove the dirty water with the oldest sponge into the dirty water bowl. Keep cleaner, newer sponges as a 'wet sponge' (to lift the grease off your stone) and a 'dry sponge' (to keep the water film nice and lean). Have one bowl full of clean water which goes onto the stone, and another for dirty, greasy water that comes off the stone.

Briskly roll out the ink onto the nap for about six rolls and then make six rolls onto the stone in all direction - or until the image looks like it did when it was greasy (it's useful to have a photo to compare notes). Use slower rolls to get more ink onto the stone and faster rolls to have less ink on the stone. Remember to keep the entire stone damp when rolling, using the wet sponge followed by the damp one. If the stone is too dry wet and wipe it before ink sticks to the stone. If it does stick to the stone, wet and most of the ink will come off again.

Proof print. Get two pieces of new newsprint torn down to printing size (one as a backing sheet, one as the printing paper). Put them on the inked stone, tympan (backing plastic) down, grease, and print. The first proof will be light. Label P1 for the first proof. Wet the stone and roll up again, using 6 x passes on different angles. Proof two should come out darker and label P2. Proof three should do it, label P3.

Second etch. Gum the whole stone again. Make up the 50/50 etch solution again and etch three times like you did for the second etch. You make need to etch some areas more heavily, or go lighter on some parts, and you can adjust the solution to get the best results from this second etch. Talc and then buff with a clean cheese cloth to create a gum barrier.

Note: you don’t need to go though the proofing process before the second etch. This last litho, I didn’t - and it was a simpler process.

Printing

Don't print until you have let the second etch do its thing for at least a few hours, and preferably overnight.

Whilst waiting you can get your art rag paper ripped to size and prep for any coloured inks or chin colle you might want to use. Remember, unlike some other printing processes, you don’t need to soak the paper before printing.

Before you print, use your burnishing tool to mark a 't and bar' where the paper will need to align onto the edges of the print. The template stencil for borders and the steel ruler will help with this task. By doing this, all of your editions will be registered the same way. Also, you can put lines on the backs of your paper to ensure that they line up with the 't and bar'. Again, Peter Lancaster's book has an excellent diagram:

To print, get 10 x ripped down newsprint sheets and two bowls, one full of water and the other empty. You need two sponges, one clean and the other 'dirty'. Have the ink slab and press set, ensuring the tympan and scrapper fit the stone.

Gum and buff the stone. Put one your gloves and glasses, turn on the exhaust, and use a rag to rub turps lightly off the stone. The ghost image will come up. With a new rag use the wash out solution on the image part of the stone and rub in the grease again. Use water and the dirty sponge to clean off the grease. Roll up with ink and use the clean water and sponges to get a lean amount of moisture on the stone again. Use a Bright Boy eraser or your finger to remove marks. Finish on a roll, not on a sponging, or you will leave water streaks on the print. Use two newsprint papers torn down for proofs again. Roll 10 x 4 rolls so forty rolls all up on the stone for each proof - moving the roller around for even coverage of ink. If you put 30 ml of gum arabic into the water bowl it will help keep it all clean and stop ink build up. Setting the press really well also stops ink build up.

After you have built up enough ink on your stone from the two proofs, you are ready to print on your nice art paper. Now do 5 x 10 rolls - so 50 passes when inking up the stone to ensure the darks are nice and juicy. Remember to wet and sponge down the stone after each set of ten rolls to ensure stone doesn't dry out. Align the T and bar with the nice paper lines and print. Ensure after each print your are hasty in sponging down the stone again. Keep doing this until your print edition is done!

Press the prints overnight.

Chin colle

Experiment with chin colle by gluing and drying one side of some coloured rice paper with rice glue. I cut it or tore it down to size and spritzed the glued side until the paper relaxed. I then placed it, glue side up, onto the inked stone. The art paper was then placed on top and then the stone was printed like normal. I quite liked the different effects of the chin colle. I also tried different variations of this print by using different coloured art paper.

Transferring a digital image or photocopy to stone

To transfer a digital image, photocopy the image to paper to black and white, ensuring that the contrast is HIGH! Remember that the image on the paper doesn't need to be reversed because it it will reverse when it is applied to the stone. Get Thinner from the Solvent Cabinet and rip down lots of newsprint to just a bit bigger than the size of the image.

Have set the stone on the set press and have your gloves and the studio exhaust on. Put the photocopy on the stone, printed side up. Put on five pieces of newsprint over the top, wet with thinner and cover with dry sheets. NOW WORK FAST! Cover with the tympan (there is a specific one allocated to digital transfers) and run back and forth through the press five times. You can carefully peel up an edge to check that is has transferred. Hopefully you have a successful transfer on your hands. If not, pour more thinner on the papers and run through the press again.

After this, go through the process of etching before printing. Note that etching can require a stronger etch ratio for digital processes.

I drew over and scraped back elements of the digital transfer on two of my later lithographs this semester. I have realised that whilst I appreciate the use of digital processes, for me, the beauty of lithography comes in the organic hand drawn elements of the art form. I also noticed that digital transfers tend to print in more grey tones and the superb rich blackness of the lithography prints are lessened in the process. I feel that in the future I will rely less on digital transfers and otherwise work more on my hand drawing onto the stone.

Printing in colour

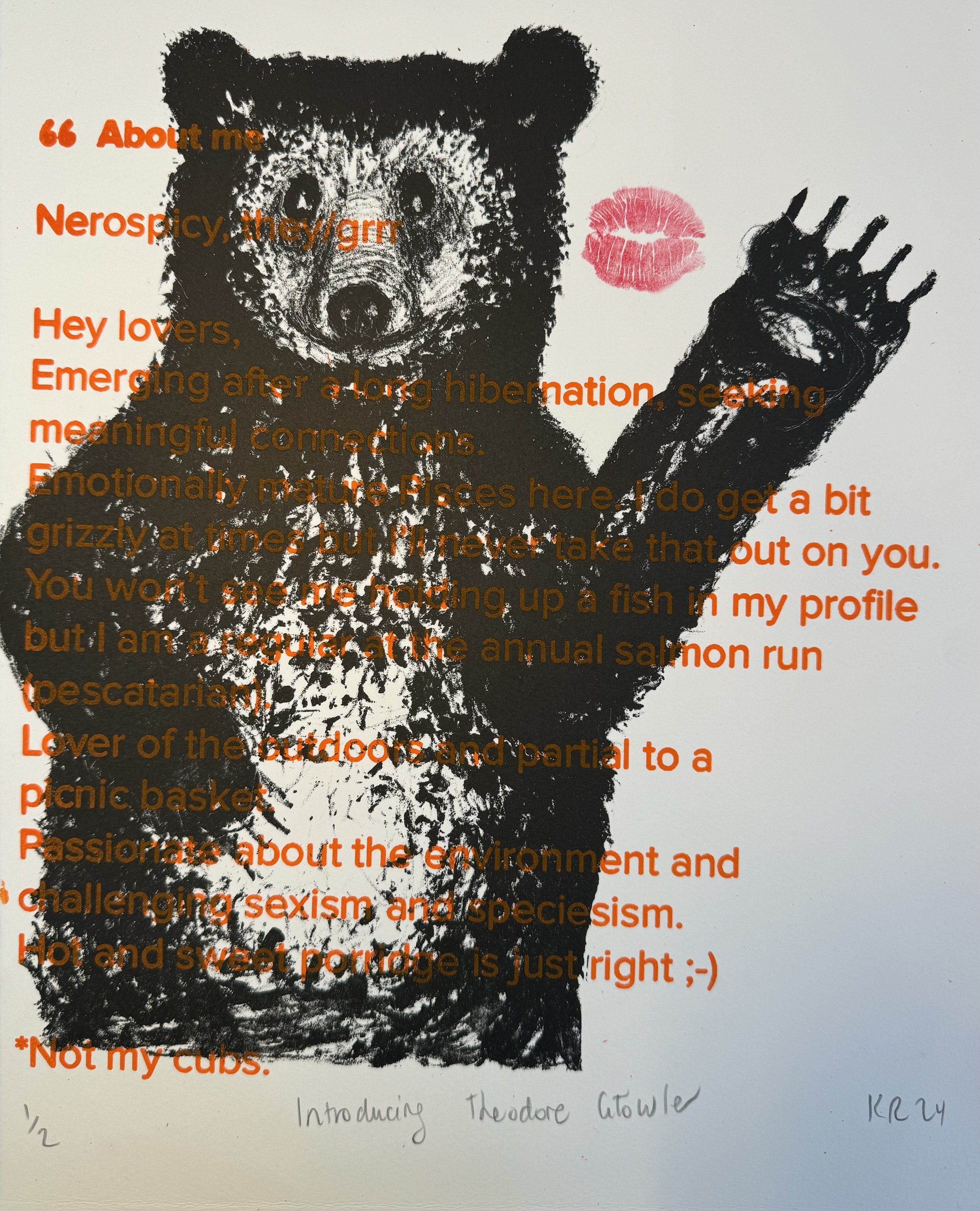

Spend time mixing the colour ink that you want. To print with colour, during the 'turps and bitumen' stage, I used turps and then coloured ink rubbed into the stone to build up the colour. When rolling up for printing also, I didn't use the nap roller because they are only for black litho ink. I used instead a more rubbery litho roller to apply the ink. Because the orange colour was a lot lighter than the black, I had to work a lot harder to build up the depth of colour. I tried it over a couple of weeks to get the effect right.

At the end of printing also, you need to replace the coloured ink with black ink because it doesn't dry out as much as colour ink. Do this by gumming, turps, bitumen, flooding with water, rolling up in black ink, drying with a flag, talcing, gumming, and buffing your stone before putting it to bed.

It took work to nail this technique but I really like the effect of the coloured ink for litho and would like to experiment with this again in the future.

Putting your stone 'to bed'

If you intend on printing on your stone again, you need to do these things before you put it 'to bed': ink up in full, dry, talc, gum and buff. Cover with a piece of paper when in storage so dust doesn’t settle on it.

Graining away your image

When you are finished with your stone and no longer need to print from it, you should grain off the image for the next person to use. Note in the register if there were any quirks (wedging or hollows) the next artist should be aware of.