UNPRINT RISING

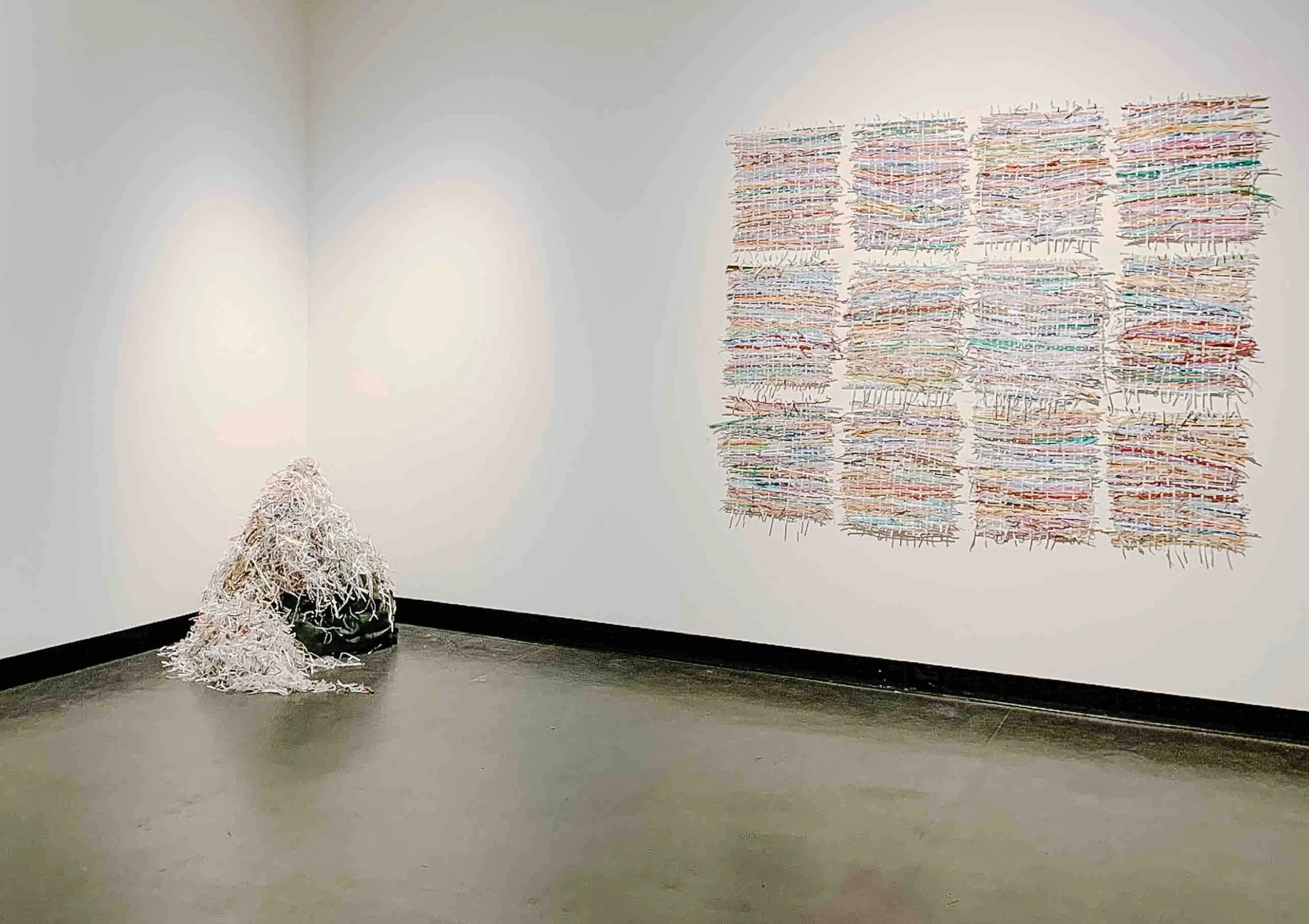

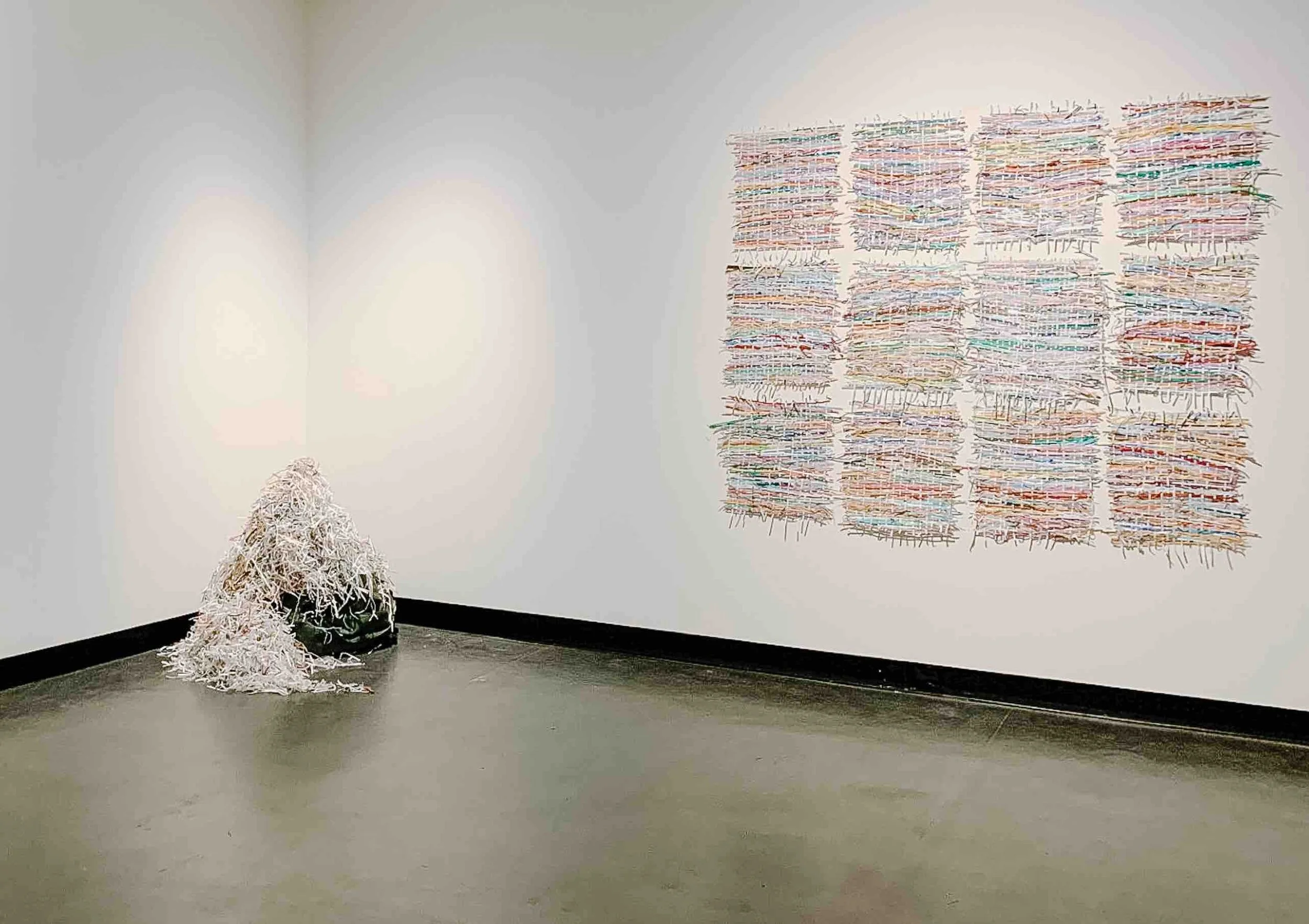

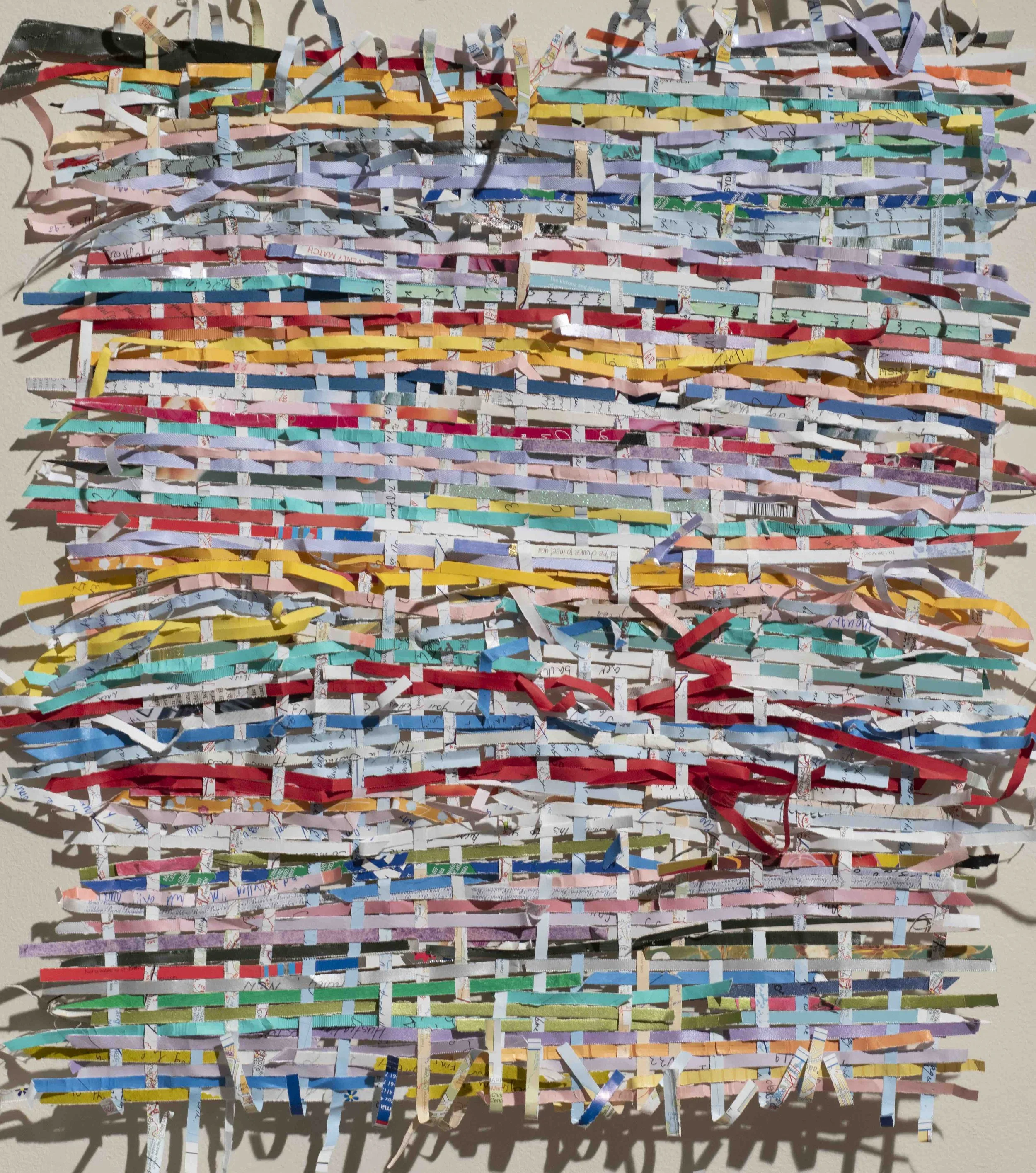

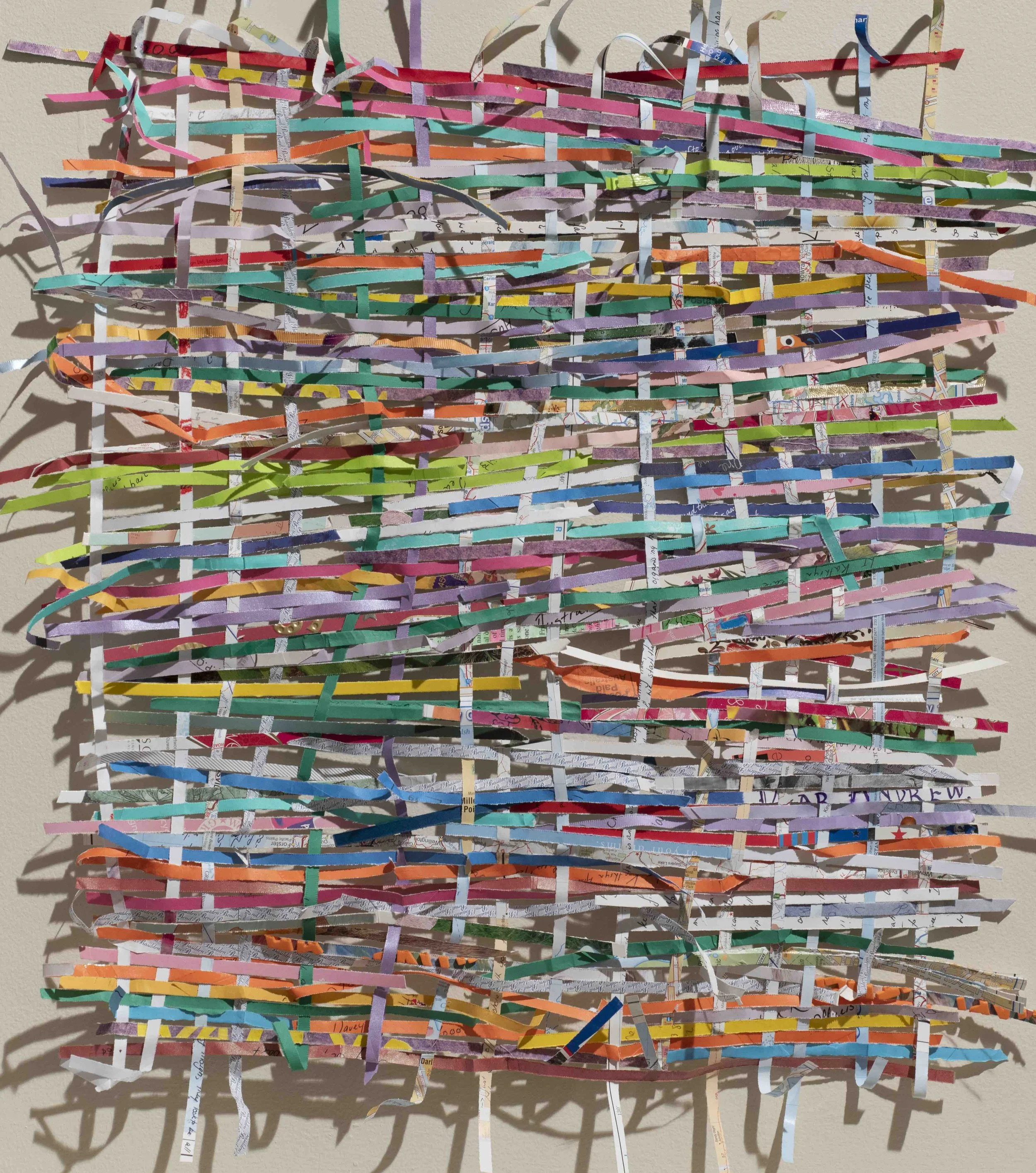

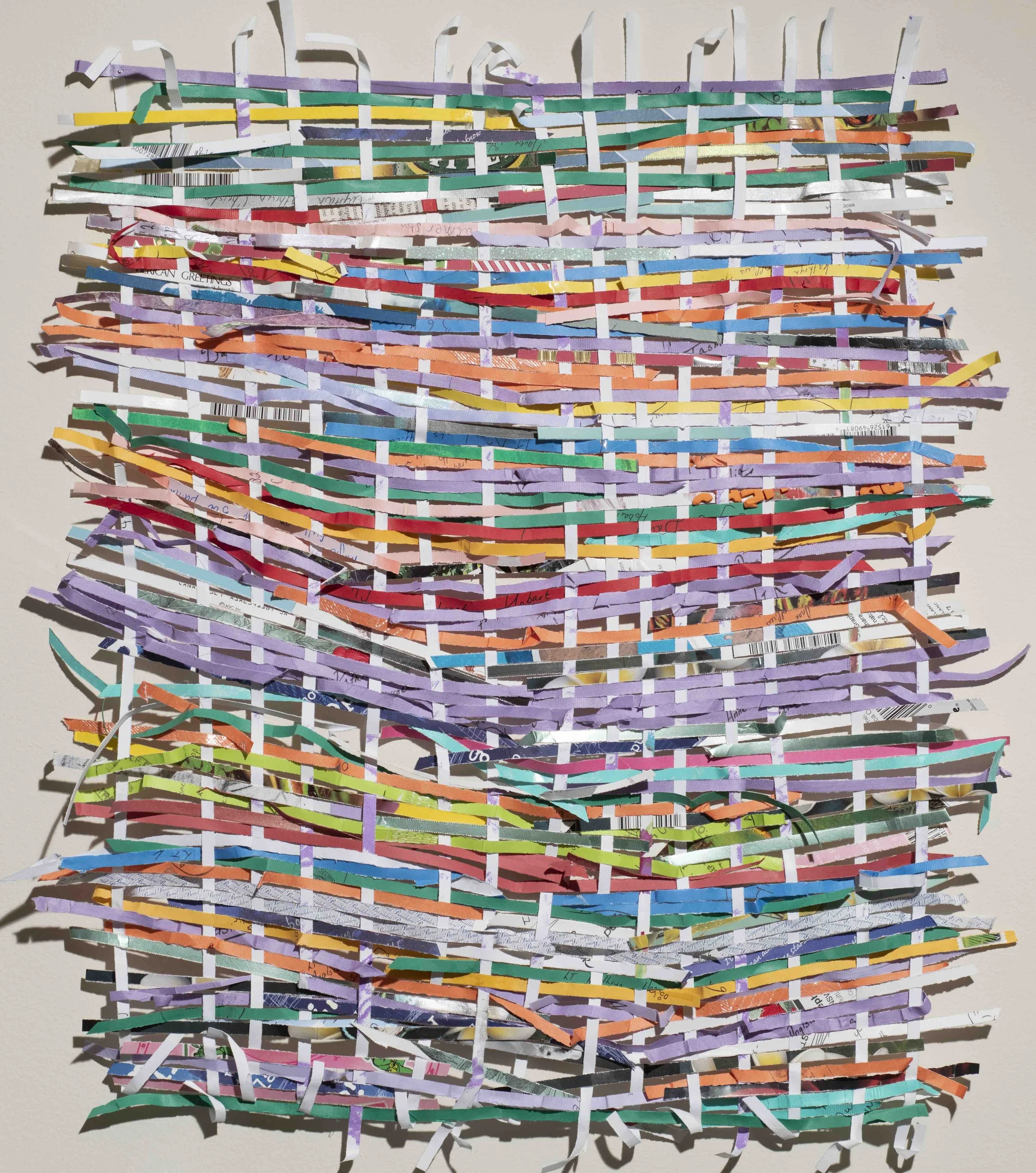

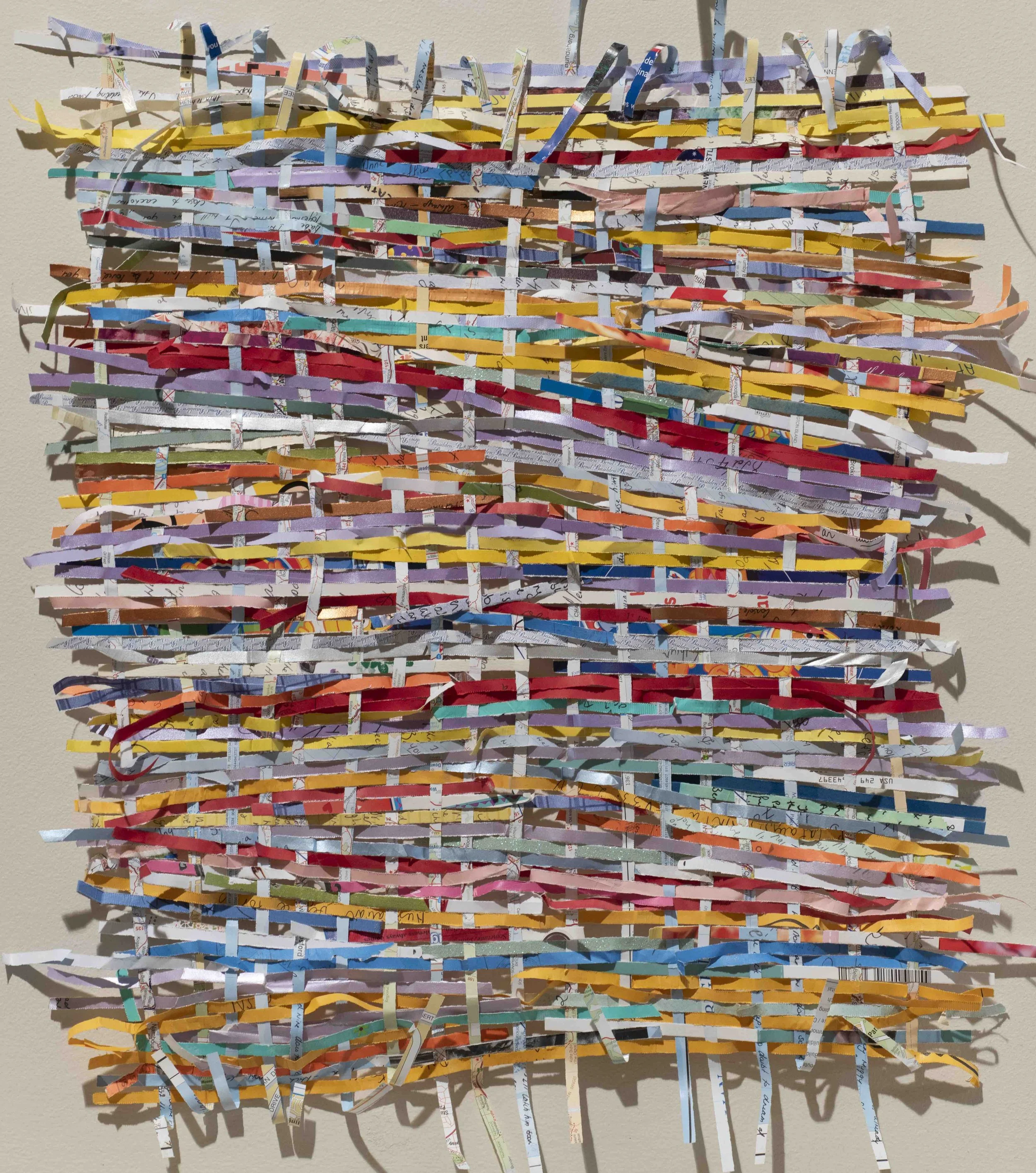

In 2017 my abusive husband, a veteran of the Australian Army, died by suicide. Death has a paper trail, particularly when that death is a direct result of the impacts of war. Unprint Rising explores the imprint of trauma by breaking down and creatively reinstating 365 love letters. Psychoanalyst John Bowlby’s fourth stage of bereavement, ‘reorganisation’, sees the mourner realise that whilst their old life is changed forever, there can be a positive ‘new normal’. My weavings of re-organised print matter are an allegory that offers a way to see that all is not lost in the vast ‘shredded-ness’ of the ‘unprint’.

Shown at:

Experimental Print Prize as a finalist, Castlemaine Art Museum October 2023- February 2024. Scroll down for the transcript of my artist talk on 13 January 2024

Castlemaine Art Museum Artist Talk 13 January 2024

I was honoured to be given the opportunity to give an artist talk at Castlemaine Art Museum, site of the Experimental Print Prize, where I was proud to have my Unprint Rising artwork accepted as a finalist. It was fantastic to present with fellow artists, Kelly Manning and Deanna Hitti. Thank you Anna Schwann for doing such a great job at coordinating and moderating the day, and also James McArdle for his excellent work at documenting the event via the transcript and photos below.

Anna: So everyone I’d like to welcome Kat, Kat Rae,

Kat: Thank you everyone for coming. I did this work, it’s called Unprint Rising - I did change the name to get into this prize ... [laughter] …it is part of this discussion about print and it’s anti-ness as well. Again as Kelly indicated, I've a military background as well. I joined the Army after high school and spent 20 years in it. And in that time I travelled all around the world plus I should note a trigger warning to this; it's also about domestic violence and war and suicides.

So in my time, the Army, I met a man who are married and we were married for ten years. And in that time, these are all the letters we wrote to each other. These letters came from back and forth from different parts of Australia to the Middle East and back to Darwin to Hobart, back to Melbourne. It was a relationship that had lots of highs, but it also involved domestic violence and coercive control. And in it, after I escaped the relationship, he suicided.

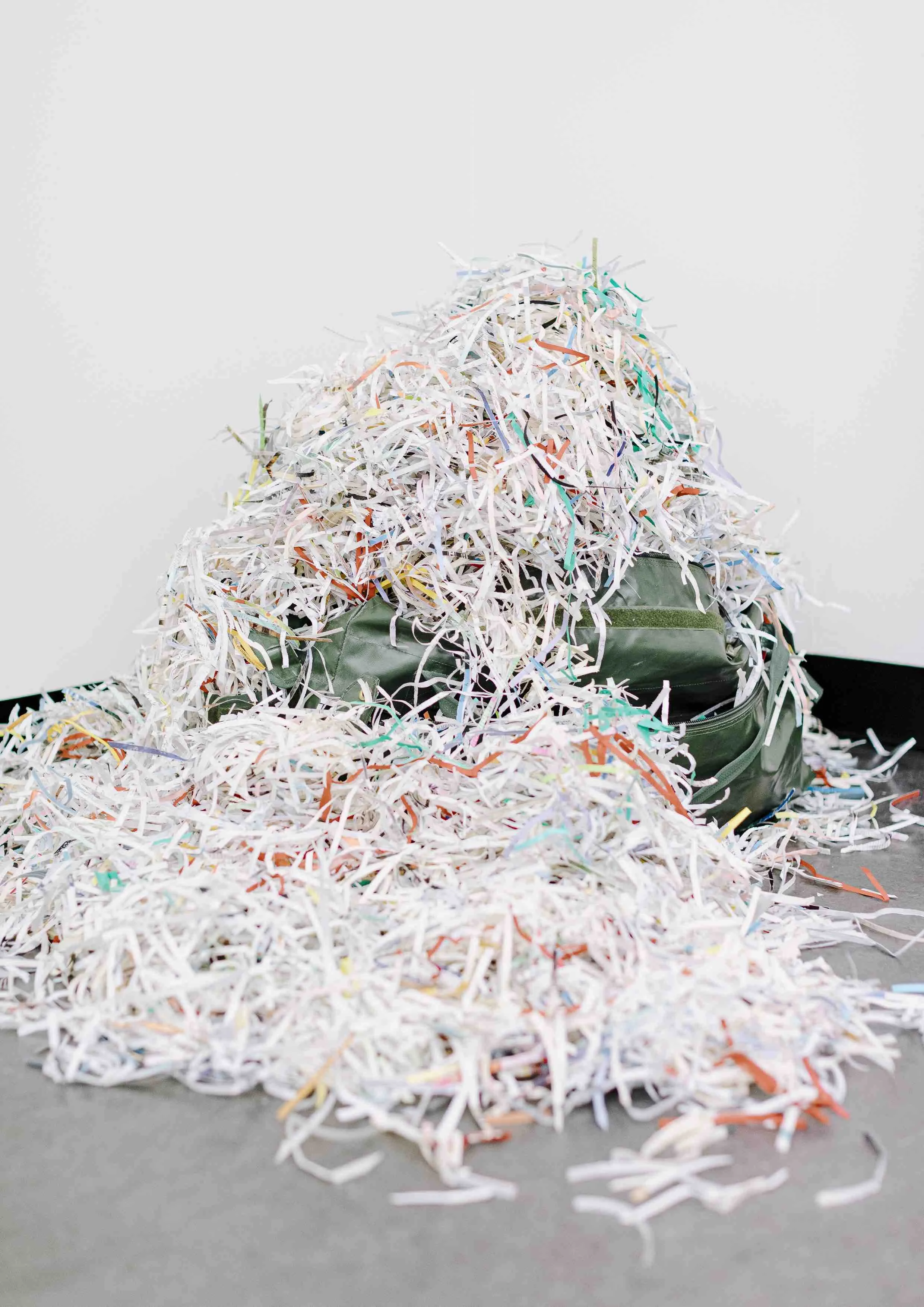

So in this work is one of our army bags which has again traveled all around the world with our deployments. And the letters which we shared, which I first of all, when I wanted to deal with them, I guess anyone who knows what it's like to have someone in your life who dies, you are given a kind of archive of their life and I'm really interested in archival work and monuments and my work explores the patriarchal sort of white supremacy idea that we have about war commemoration in Australia.

And I'm very interested in sort of offsetting that because for me as a veteran as well, it kind of ignores particularly women and children, people of colour, and the environment, and that's where it asks us to question the military industrial industrial complex and the way that it affects our environment and the people. So I had a massive back catalogue of uniforms, military work. I've got another work, it’s like a stack of military paperwork from Andrew's military history, which is actually my height. So I’ve done another work with that. But this one was kind of talking about the personal and the real and our relationship and how to come to terms with loss and absence and trying to restore yourself.

The psychologist John Bowlby, you probably know him, in the sixties wrote about grief and loss and talked about the fourth stage; that being reorganisation. I just felt like I couldn't keep this catalogue of Andrew's life with us any longer because I needed to, yeah, kind of handle it, in a way, in a way that an artist maybe could contend with such things.

So I, first of all, go through all his letters. I thought initially “I’ll keep them for ever, give them to our daughter.” But after a while, I sort of thought over that, I could see coercive control in them and red flags and warning signs. I just thought, I’ll keep some of the best ones for her, but I really actually wanted to redact them and stencil over them and talk back to them in a way I couldn’t when he was alive. So I started doing that, but it didn't feel enough, and in the end I decided to shred them, which is pretty empowering actually. And that kind of spoke to secrecy and again redaction, and institutional hiding of truth, in particular about war and how we never get to see what what the truth, the history, is.

It took so much time to do that and I enlisted friends to help me as well. And it kind of became, I guess, a communal thing where in the studio we would shred a bit together and it was kind of really folk, and in the end I had this giant pile of shredded things and it looked like a mountain—again talking about environmentalism and of mountains, I guess, of being on the move in steep, slow time for a long time.

Aldo Leopold writes about mountain time; there's been deep time slow, thinking about the interconnectedness of us, but with climate change happening and the destruction of our environment, we see mountains moving faster and they traumatise, you know, there's been destruction, war has destroyed mountains so has colonisation, so time is moving faster, even mountain time.

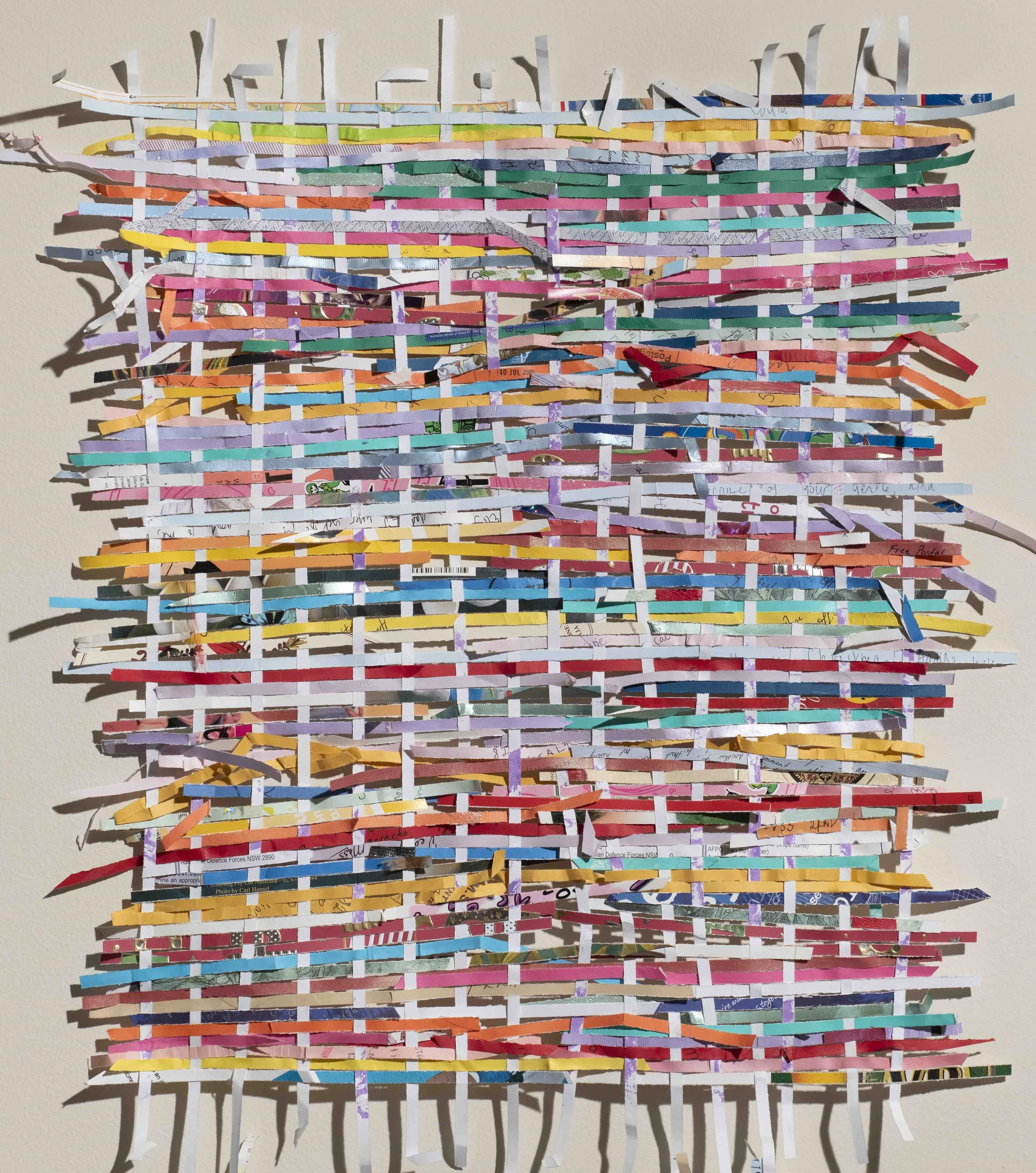

And I was interested in time of healing and time in trying to restore what happened. So, yeah, I initially called this Mount Coercion…as I said I kind of changed it for the purpose of this exhibition [laughs] And then I started joining them together, like in the Stasi, they have all, yeah, secretly taking information off, observing all their citizens, they shredded everything after the fall of the Stasi and the people now are just trying to stitch together what had happened; it's painstaking work. and I started to be inspired, but then I wondered what would happen if I stitched together some of these, but kind of in a Frankenstein way and one of my friends said, wow, that looks like it could be a weave. And initially I thought I could never weave…something in me was maybe I was slightly suppressed, I guess I didn’t want to go with something so sort of feminised in my art, but you know what, I kind of leapt into it. It’s really interesting; occupational therapy started after World War One, and they taught the veterans how to weave. I was like, my God, this is so therapeutic and as I was doing it I was watching the Royal Commission hearing into veterans suicide, and I was listening to all these stories and I just like, “Wow, I'm not alone actually, my story is one of many.” And I found long pieces in the shreddings of this map, which Andrew had hand written on, to show his journey from Hobart where I was living off to Darwin, and it had annotations of where he’d stayed and adventures he’d had the four-wheel drive got flooded at one point, all these things, and they were excellent kind of longitude and latitude of the framework of the weave.

I picked the most colourful parts of the pile to kind of build, you know, so some happiness in the relationship as well and I wanted that to be kind of recognised too; there’s twelve of them. I kind of ran out of enough colourful bits by that stage, but I kind of felt like this is again, time there's twelve months in a year, this has got 365 letters, I felt like the kind of the slow burn of war, of domestic violence, of healing, of kind of coming together at the end of it, kind of create something that's lighter after such heaviness.

Anna: That really translates in this work, like it's a real full circle journey. And I do want to say thank you as well, because this is obviously a very sensitive and intimate part of your life that you’re letting us in on, so I want to just recognise that, and appreciate that is a really incredibly strong thing to do and to work through all of this in the way that you have. I mean, I love the sound of you bringing your friends into the studio to work on pieces of it together to support together to go through all the opportunities that came up through that reprocess as well, because when I see this work, I do sense the lightness which kind of speaks to your journey, you know, speaks to what you've really processed and gone though, so what an amazing thing to be able to channel that through… these are quite carnivalesque with their incredible bright colours when they speak of joy. There's something about that weaving process, which is also like a joining and when you spoke earlier about the reorganisation, you know, this is something that you can now take it to own hands and reorganise it in a way it feels natural, in a way, it feels like it’s a true essence.

Kat: Thank you. Yeah. So Bessel van der Kolk writes about trauma and how the body keeps score. He talks about the weight of memory and the heaviness of it, and also the imprint of trauma, I guess all those words, especially ‘imprint,’ have a lot to do with printers and the way that we work.

And I was really interested in kind of subverting that idea and creating something light at the end. I kind of got to where I did start thinking this is kind of very much the process art where you're interested in the labour of what you're doing and it feels right to keep going and at the end you come up with something. But yeah, that's very much part of it too.

Anna: Well, I’m curious in terms of obviously, through subject matter. You know, your experience with ties and experiences has obviously come out in terms of subject matter through your artwork. So when we speak about process, do you feel like that [inaudible] your process?

Kat: Yeah. Yeah, I can. Kiki Smith wrote about art being the end product of your process, something like that, but yeah, I really love the idea that the end product being the process that the result of your process and your processing as well. And I guess while this is such time consuming work in that time I was able to kind of read and listen and think and really kind of come to terms with what happened. In a way I would express my anger through the shredding, I could kind of piece things together at the end of it, I could keep things secret that I wanted to keep secret and broadcast other parts. I got to, as opposed to a lot of trauma survivors I guess you know, the disclosure and enclosure, what you get to say or not say, isn’t always given to you. But in this, I was kind of given the power and authentic sort of autonomy to go to do that.

Kelly: It’s a really strong work. And I really see that thread of military and post-traumatic stress. And obviously the therapeutic process of the weaving, but the, the order but the non-order is really interesting. And then the haywire, of you know I guess the down points of the post-traumatic stress that’s really powerful.

Kat: Judith Herman is Van der Kolk’s kind of peer, she's a feminist psychologist that she was also talking about PTSD being more common in women and children, than it is in men. But it is only the combat veterans, particularly the Vietnam veterans who kind of brought it to the fore. Thank goodness they did. But the truth is, still women and children have PTSD in greater numbers mostly at the hands of men and their behaviour . And for sure, I've got PTSD but it's more to do with the domestic violence and coercive control than my war experiences. So, yeah, I definitely wanted to kind of bring that into it as well.

Kelly: Yeah, and I think that's really great. I know that the Vietnam veterans get a lot of exposure and a lot of acceptance around post-traumatic stress. So yeah, it's really good to expose the other side of that. It's it's, you know, that its quite broad.

Q: I just want to say I'm so glad that you embraced the feminine art of weaving, I’m so grateful for that and the use of these personal archives that go into the process and the personal transformation in the material. And it's just a it's a very integrated work, I feel, when you stand there and talk about it…I think that's rare

Kat: Thank you

Q: I just want to say thank you very much for being so honest about coercive control and DV, very few people want to talk about it. This is my how I feel about this work is, through your process, it doesn’t seem nostalgic or sentimental in any shape or form, you’ve removed that completely and it’s just power, it’s just remarkable. And I just want to thank you for it.

Kat: Thank you

Q: I just think it's wonderful these talks because how many times have I been in here and I walk past and sort of read about it and it just doesn't mean anything until you actually talk about it. But thank you for coming

Kat: Thanks for listening.

Anna: I should mention at this point as well, that Kat also has some really incredible writing about this work in particular, some other works as well, with some really great documentation about the process along the way, which is on her website, which is absolutely fascinating to look through because I think that's something that is so important, people who are great documenters, in that sense, it's wonderful. It's so beautiful to be let in on that process and the thoughts behind it so there's something to be said to be following the unraveling along the way. Yes. And that is definitely worth watching.

Kat: Yes my website’s katrae.net easy to remember, and I've got some blogs there that talk about process of it as well. I've got some beautiful photographs of these weaves as well by a local photographer Ian Hill just in case you're interested

Q: [inaudible, about making a book]

Kat: Yeah I did make a book…I took one of these weaves and I turned it into a screen print, like I used a stencil of it to make a screen print, and I made some beautiful screen prints by dragging some colours across to get the idea of the weave, but with just the shape of the weave as well and then I made so many of them, and they’re on beautiful paper, so I made a book out of them. And I also looked at Venetian blinds, you when you kind of feel terrible and you’re grieving and you look out through Venetian binds and think “Oh the world’s out there.” So they also spoke of happiness because they’re all so bright and cheerful, but also a bit of that as well.

Anna: Yes they really live many lives and I love that the process of taking it through all these different stages and places—quite amazing…

Thank you so much for sharing Kat.

{Applause]